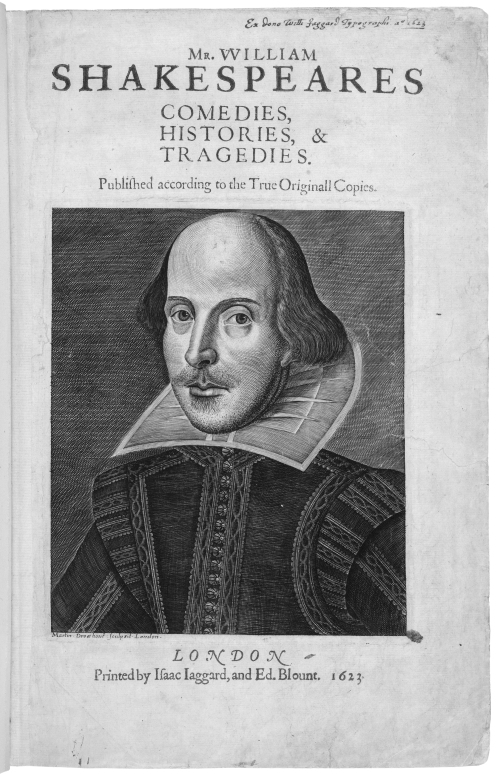

This year, in honor of the 400th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare (on April 23, 1616), the Folger Shakespeare Library has organized an extraordinary tour of First Folios from the Folger collection to all fifty states. Steve Grant, author of our widely-admired Collecting Shakespeare: The Story of Henry and Emily Folger, has undertaken an similarly ambitious speaking schedule that will take him to several of the hosting libraries, museums, and institutions participating in the tour. We’ve invited Steve to provide regular updates as he follows the First Folios around the country, speaking about their important literary and cultural history the extraordinary legacy of Henry and Emily Folger.

Guest post by Stephen H. Grant

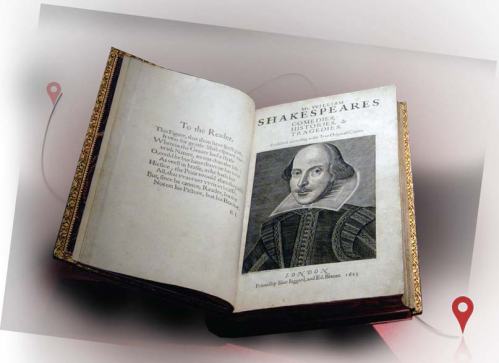

On display in the New Mexico Museum of Art during February, 2016, Shakespeare’s First Folio open to the “To Be or Not To Be” speech in Hamlet.

Partnering with St. Johns College in Santa Fe, the New Mexico Museum of Art won the competition to host the First Folio Exhibition from February 5 to February 28, 2016. While the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC––only two blocks from the U.S. Capitol––required that host institutions organize at least FOUR events during the exhibit, the Museum arranged FORTY events.

One event was the Shakespeare Treasure Hunt. Youngsters picked up a free treasure map and followed clues based on quotations from the Bard that led them downtown to declaim the lines to local merchants. Visitors from the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art put on a workshop on the breath, sound, and articulation on Shakespeare’s sonnets, including practice in reading Shakespeare out loud. The Museum organized a day of love and art where participants created cards, heart ornaments, and Valentine’s Day collages inspired by Shakespeare.

Director of the Palace Press at New Mexico History Museum in Santa Fe, Tom Leech, demonstrates a wooden hand press like those used in early 17th century England.

Of all the First Folio Exhibit venues, New Mexico is the only state where a government was operating when Shakespeare was alive and writing The Tempest. Across the street from the New Mexico Museum of Art is the New Mexico History Museum, created in 1610 as Palace of the Governors, when Spain established its seat of government in Santa Fe to cover what is now the American southwest. It is the oldest continuously occupied building in the United States. Award-winning Palace Press printers Tom Leech and James Bourland mounted a multi-part exhibit where they printed facsimiles of a First Folio page using a replica Gutenberg wooden hand press. Visitors were invited to make their own prints to take home.

Steve Grant outside New Mexico Museum of Art before his talk to 200 enthusiastic Shakespeare addicts.

In Conversation with John F. Andrews, President of the Shakespeare Guild, I spoke in St. Francis Auditorium on Collecting Shakespeare and the First Folio to 200 Shakespeare enthusiasts come from the area to catch a glimpse of the First Folio on display in an adjacent room and opened to the “To Be or Not To Be” soliloquy from Hamlet. The Shakespeare Society bid adieu to the First Folio on February 28 by performing familiar farewell scenes from Shakespeare.

Stephen H. Grant is the author of Collecting Shakespeare: The Story of Henry and Emily Folger, published by Johns Hopkins. He is a senior fellow at the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training and the author of Peter Strickland: New London Shipmaster, Boston Merchant, First Consul to Senegal. We expect Steve’s next report on the First Folio tour after he speaks in San Diego on June 22 the San Diego Public Library.

STEVE’S 2016 FIRST FOLIO TOUR

April 15, Noon

The Association of the Oldest Inhabitants of D.C.

Capitol Skyline Hotel, 10 I St., SW, Washington, D.C. 20024

OPEN TO MEMBERSHIPTom Leech designed and printed this “WANTED Willy the Kid” poster displayed in many Santa Fe store windows during the residence of the Folger Shakespeare Library’s Shakespeare First Folio.

April 18, 10:30 am – noon

Live & Learn Bethesda Talk

4805 Edgemoor Ln, Bethesda, MD 20814

REGISTRATION REQUIREDJune 21, 11:00 am

Calvary Presbyterian Church Seniors Program Talk

2515 Fillmore St. San Francisco, CA 94115

PRIVATE EVENTJune 22, 6:30 pm

San Diego Public Library Talk

330 Park Blvd., San Diego CA 92101

FREE & OPEN TO THE PUBLICJune 23, 6:00 pm

San Francisco Public Library Talk

Main Library, Koret Auditorium, 100 Larkin St, San Francisco CA 94102

FREE & OPEN TO THE PUBLICSeptember 29, 6:30 pm

Cathedral West Condominiums Talk

4100 Cathedral Ave. NW, Washington DC, 20016

FOR RESIDENTS AND GUESTS

You must be logged in to post a comment.